From Liberation Movement to Neoliberal and Extractivist Betrayal: the ANC and FRELIMO

The most vital reminder of how national liberation movements’ exercise of power contradicts their former ideals is the durability of radical and often anti-imperialist narratives in times of political panic.

It is then that those in power attempt to disguise how the spoils of liberation are being devoured by corrupting neo-colonial forces both within and without the nation.

It is then, too, that the international threats are conjured up (sometimes together with ethnic fear-mongering), so as to distract attention from the party’s immediate failings. Two Southern African countries, Mozambique and South Africa, boast among the world’s most vivid examples of this tendency to ‘talk left and walk right.’

In South Africa, the more the African National Congress (ANC) is threatened as the ruling party, the more this populist tendency will be given voice. This happens just as at the time that genuinely destructive neo-colonial forces – especially those in the financial markets insisting on fiscal austerity – amplify the society’s already extreme contradictions.

By the end of 2022, the ANC will have governed South Africa for more than 28 years, after the movement’s unbanning in 1990 was won through exceptional protest and coordinated international solidarity. Economic, political, cultural, social, environmental and other policy changes adopted during the 1990s were profound in many respects, especially in terms of the ANC’s most celebrated success: one-person one-vote in a unitary state, the primary goal of liberation.

But the ANC soon became a party run by the elite which moved quickly towards neoliberalism and opening the market. One of the main vehicles for the party’s durability and the breadth of loyalty by its members was what became known as ‘tenderpreneurship’: a vast web of state contracts given to cronies.

Yet in electoral terms, the ANC retained enormous, consistent popular support thanks to loyalty that was based in part on its liberation movement prestige and in part on subsequent patronage power.

In February 1990, the apartheid regime unbanned the liberation movements. The ANC’s leadership was consolidated in a 1991 conference that made Nelson Mandela the party president, and current president Cyril Ramaphosa the General Secretary. In different ways, both succumbed to what Ronnie Kasrils has called the ‘Faustian Pact’ with local and global big business which catalysed South Africa’s neoliberal era.

In 1999, Thabo Mbeki took Mandela’s place as state president and served until September 2008, followed by Jacob Zuma. Both were in the spotlight during the exposure of the ‘Arms Deal’ in 2011, a massively corrupt deal that cost the taxpayer R142 billion ($8.2 billion at today’s rate) to pay off German, French, British and other arms companies for submarines, corvettes and other military equipment.

A lot had changed since the writing of the Freedom Charter of 1955, written by the Congress of the People which promised that the “The mineral wealth beneath the soil, the banks and monopoly industry shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole.” Instead, already in 1994, the ANC’s Reconstruction and Development Programme’s wide-ranging strategies for transformation were ignored. In contrast, a listing of the dozen most damaging 1990s ‘Faustian Pacts’ between the ANC and capital (to quote former Intelligence Minister Ronnie Kasrils) included:

- repayment of the US$25 billion apartheid-era foreign debt, which denied Mandela money to pay for basic needs of apartheid’s victims (October 1993);

- borrowing $850 million from the International Monetary Fund, with tough conditions that included rapid scrapping of import surcharges that had protected local industries;

- joining the World Trade Organisation on adverse terms, as a “transitional”, not developing economy, in turn destroying many clothing, textiles, appliances and other labour-intensive firms (June 1994);

- lowering primary corporate taxes from 48% to 29% and maintaining countless white people’s and corporate privileges (1994-99);

- relaxing exchange controls, which led to sustained outflows to rich people’s

- overseas accounts and a persistent current account deficit even during periods of trade surplus, raising interest rates to unprecedented levels (March 1995);

- privatising parts of the state, such as Telkom, the state-owned telecommunications company (1997);

- permitting most of South Africa’s ten biggest companies to move their headquarters and primary listings abroad, leading to permanent balance of payments deficits and corporate disloyalty to the society (1999).

These decisions led South Africa to disaster. Unemployment was at 16% during the 1990’s. Then it increased from 25% in 2015 to 28% in 2021. And 30 million people still live in poverty. Again and again, South Africa is cited by researchers as having the world’s worst inequality, and Johannesburg is measured as the world’s most unequal city.

The socio-economic grievances of the vast majority soon became profound and unresolvable. Today uprisings still continue to escalate – South Africa has been dubbed the ‘protest capital of the world’. People are burning trains and blocking highways and burning tires for access to toilets. In August, four people were killed, allegedly shot by police in a protest in a Johannesburg township demanding lower costs of electricity and basic services. And later that month thousands around the country took to the streets to protest the high cost of living. The disease of xenophobia has continued spreading, with people blaming people from other African countries, including asylum seekers, for their poverty. This has led to extreme violence against immigrants.

Earlier this year, former Thabo Mbeki warned current President Ramaphosa that the country is headed towards its “own version of the Arab Spring”. Over the last few years, for months at a time, South Africans have been dealing with loadshedding, scheduled power outages. Even hospitals and schools are not spared from these power cuts, and businesses who can afford it have had to purchase generators. All the while the South African government is spending billions of dollars on overseas fossil fuel investments and is the third highest coal producer in the world.

In South Africa, straight after the creation of the Republic, some politicians – most of them former freedom fighters – had an uneasy relationship with the dominant white business bloc. But many of these men and women readily circulated into financial institutions and mining houses before or after their state service, including Rothschilds, Goldman Sachs, Allan Gray Investment, ABSA Bank, Shanduka/Lonmin/Standard Bank, AngloPlats, and BHP Billiton.

State and private extractivism became so closely linked, that they led to disasters like the Marikana Massacre at Lonmin Platinum mine of 2012 which left 34 striking mineworkers shot dead by police. Ramaphosa, then member of the ANC’s national executive committee, held a 9% ownership in Lonmin, and the massacre was catalysed by Ramaphosa’s urgent emails to the police minister to send more police to the protests.

Today, South Africa has 549 mines, owned by 174 people, and is the world’s top producer of platinum and third largest producer of coal. The extractive industry has brought destruction and disaster. Entire generations of mineworkers have contracted lung cancer and silicosis, hundreds of thousands have lost their homes and livelihoods from displacement, and in 2013 already coal-mining town Witbank was named by the European Union as having some of the most highly-poisoned air on the planet, where respiratory illnesses among children are frighteningly common.

This travesty is not unique to South Africa. In neighbouring Mozambique we see the same downward spiral once the country became free, the same promises and dreams destroyed by neoliberal agendas.

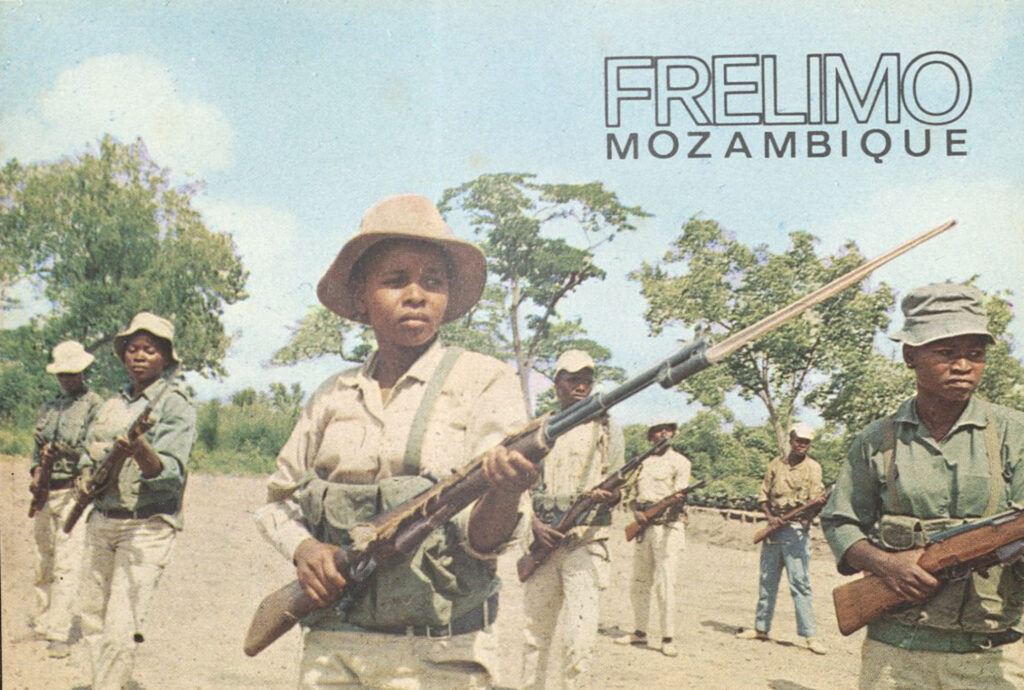

After decades under Portuguese colonialism, the country only gained its independence in 1975 when many other African countries had already obtained their freedom, some decades earlier.

Frelimo (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique), a movement with a Marxist-Leninist ideology created in 1962 to fight the colonial system, became the only party and the sole ruler of Mozambique.

Under the communist system, one year after independence the government nationalised property, education, health and many manufacturing industries, based on the ideals to end poverty and to become a socialist country, exemplary to the world. The people were ready to build an independent country from the ground up, where everyone had equal rights, where decades of poverty, slavery, racism, human rights abuses, inequality, extractivism and all injustices would be a thing of the colonial past. They had a dream and believed in it.

So began the mass mobilisation characteristic of communist countries, with Frelimo propagandising itself as the only legitimate party and the liberators of the country. With the dream in place, it had huge success with the people, and this continued even when the situation morphed to one of food shortages, supply rations for each family, queues for just about everything and worst of all, no freedom to speak out against either the state or the party.

These hope and ideals meant the population was willing to make sacrifices, and did so, but could no longer look away from the frightening changes taking place before their eyes. Government began talking about the need for free markets, and foreign investment to develop the country, yet still within a proto-communist system. Those dreams and that steadfast hope disappeared.

Today, Mozambique is one of the world’s most corrupt countries. Those who were once revolutionaries and freedom fighters are now becoming dollar millionaires. They open doors to any corporation or fossil fuel company that comes knocking, allowing them freedom to take as much as they want, leaving people affected by these private projects in misery.

Government officials make speeches at major international conferences about ‘development’, and their right to extract fossil fuels, just as northern countries have been doing for centuries. They speak without acknowledging the climate crisis the country and world faces today, and their people’s rights to food, land, water, and energy sovereignty, which are being ripped away by these industries.

Today, gone is that hopeful socialist ideology and what was once named the “People’s Republic of Mozambique” that evoked such pride. The country is now merely the ‘Republic of Mozambique’, a brutal, capitalist state based on neo-colonialism and extractivism.

Frelimo still rules the country after 47 years, and it is now the third poorest country in the world, on the ten bottom worst countries in the UN Human Development Index. Only about 30% of people have access to energy, thought the country is a major energy exporter).

Mozambique is also a growingly devastated country, with huge loss of forests, mostly due to illegal logging with the involvement of government entities. Land-grabbing from rural communities to give place for fossil fuels exploitation or other foreign investment is common. The brokers’ deals and secret loans create illegal debt that has cost the people and economy billions of dollars.

To maintain this state of things, there is an increasing number of threats, arrests and disappearances of journalists and increased daily violations of human rights. Civil society space is shrinking. Right now organisations are fighting to stop a proposed law that will provide the state with greater control over civil society and undertake witch hunts of organisations they deem threatening. Activists are threatened, and it is illegal to march or demonstrate without authorisation. There is impunity for corporations and the private sector who are able to get away with what they want.

In Mozambique, just as in South Africa after independence, politicians moved into the realm of mining and fossil fuels, and the impacts have created economic disaster, deepening debt spirals and a social system that has left the people with little hope that the promises made by the liberation movement would ever be fulfilled.

The extractive industry is causing mass destruction of the environment, livelihoods and the country’s economic wellbeing, spreading its claws through deforestation, hydropower dams, coal, ruby-mining and gold across the country. Extractivism in Mozambique started with coal, when huge coalfields were discovered in Tete Province after independence. People were made to hear long speeches about how coal would bring development and a better life for all. But soon there was no clear division between government and corporations. They spoke the same language, they made the same promises, they visited communities together.

When affected communities started to raise their voices and demanded their rights under the agreements with companies, and as per the Constitution, government special military forces would be brought in to quash dissent. The first of these attacks was in 2012, and since then communities have experienced arbitrary arrests and shooting up into the air in places full of innocent children and women. Communities were impacted by the industry immediately. Mining companies cut off their access to water, and in cases where water was accessible it would be polluted. Any attempts at going to court have proven futile, not surprising when there is no separation between the state, the ruling party, the legal system and the power of corporations to continue destroying people’s lives with impunity.

In the provinces of Cabo Delgado, Inhambane and Nampula, gas drilling has been bringing monsters from across the global north, such as Total from France, Eni from Italy, ExxonMobil from the US, and Sasol from South Africa, and several Chinese, Indian and British companies and financiers, as well as the governments themselves.

Just like the way international companies such as Shell and Barclays propped up the apartheid system in South Africa, other corporations still exploit the people for their resources. And colonial powers like Portugal, through its fossil fuel company Galp and bank Millennium BCP, are major players in Cabo Delgado’s liquified natural gas (LNG) industry.

Sasol is a company created by the South African apartheid state, a regime which contributed greatly to the civil war in Mozambique. And Sasol has been extracting gas in Pande and Temane for two decades, in a deal that has lost the Mozambican government billions of dollars in taxes. The deal has also enabled Sasol to practice tax avoidance, accusations of transfer pricing by local civil society, and left communities displaced and living in severe poverty. Absolutely none of the revenues from this project have benefited the economy or people in real terms. Sasol now has concessions to explore for gas in the Angoche Basin in Nampula province, for projects that will destroy protected islands and entire communities of fishers.

Colonising powers against whom the Frelimo and ANC parties were founded are now still eating away at the substance of the countries. In Cabo Delgado, once again, none of the revenues from the $50 billion LNG projects will benefit Mozambique. In fact, they have in fact already ruined the country’s feeble financial stability. Before any gas has even been extracted, Total, Eni and ExxonMobil have already set up special purpose vehicles in Dubai which will lose Mozambique $5 billion just by withholding taxes. They have displaced thousands of people, fuelled a war that has created one million refugees and has already damaged the onshore and offshore environment, and led to irreversible climate damage which will continue at a rapid and unstoppable pace.

The rhetoric used by northern companies and states is that Mozambique and South Africa, like the rest of Africa are corrupt. This convenient lie enables them to exploit the country by benefiting a small number of elites, in the name of ‘sovereignty’. They are quiet about the way in which their own corrupt regimes put certain politicians in place as pawns, who would allow them to continue their extractive and destructive systems even when they were out of power. They are quiet about the bilateral agreements in place, and agreements with the IMF and World Bank that keep the countries hostage to northern, wealthy states.

Mozambican and South African political elites who either own, or are owned by, the fossil fuel and extractive industries, as well as the governments exploiting their resources, emphasise the need for ‘fossil fuels for development’. This narrative has proved to be untrue. Extractivism only benefited the apartheid and colonial regimes and since then has left disaster and ruin in its wake. This narrative goes as far as accusing anyone against it as being ‘anti-development’.

How often do we hear from African oligarchs and governments that those who oppose these fossil fuels are trying to keep Africa ‘behind’? They exploit the suffering of people who are still struggling because of the legacy of institutionalised oppression and colonialism. What was once a system that these former freedom fighters were fighting against, is now one that they are perpetuating, one that is keeping people downtrodden and in constant struggle. That system keeps these countries and their people, once with so much hope, in a state of desperation and poverty.