In the Cauldron of Revolution

As there are confusing notions on what constitutes system change, there is further confusion on what a revolution actually is. If there is no broad common agreement on what constitutes a revolution, it becomes impossible to actually plan or organize one. If we don’t have a relatively common understanding of how the system works, how it stands, replicates and perpetuates itself, the possibility of affecting it, let alone dismantling it, becomes null.

In the last decades, revolution has become growingly a protest chant. This is a consequence to the domination of non-revolutionary theories of change, directly connected to the overwhelming strength of the capitalist system and frailty of alternatives. Winning an election has become equated with making a revolution. Talking about revolution has become a tool of recruitment for progressive but non-ruptural movements and parties. By letting a revolution remain an abstract, undetermined and temporally uncertain prospect and event, we allow conformity in movements and parties. This gradually absorbs the idea of a revolution as an unreachable myth or, at least something to be made by others. This is so much so that many organisations, although agitating around revolution, become extremely hostile to the idea of advancing any escalation in social struggles, even when facing massive upsurge from reactionary forces or a degrading social and environmental situation.

That is why we must reject the complacency of the idea that “The Struggle Continues”. With the climate crisis we have a deadline that can’t be ignored by relying on tradition and habit. Nothing is traditional or common about the time we are living in.

Outlines of a revolution

It is a given fact that a revolution can’t be perfectly outlined in advance. Unpredictability is a key aspect because the clash of forces, organisations, institutions and people in a rupture of normality will lead to new behaviours and actions. We must address this with openness and flexibility. We can’t look at this unpredictability as a deterrent, but as another factor to be taken into account.

When we talk about revolution we are talking about a moment of absolute contradiction in society, frequently pushing one part of society against the other, in which there is a shift in power and the creation of a new hegemony in society. Some want power to ossify their position, others to break the old bones of society.

A revolution is a dialectical process of opposites: the sovereign, the state, the system, the government are the contrary of the revolutionary movement, which develops an alternative theory on sovereignty, state, system and government, its objective enemies. The revolution is the confrontational moment between these opponents.

As such, a revolution isn’t an uprising where the people, united, overthrow the system. It is also not an ecumenical moment of pure beauty that suddenly dissolves differences in society. The destruction of the oppression at the root of all revolutionary events must be an intended and methodical process, organised and planned. As such, a revolution is not something which “happens”, but something that is intentionally made.

The historical reasons for revolution have very often been connected to oppression and irreconcilable differences between classes or between groups within the same class. The issue of power and violence has always been at the core of revolution, which is why there is confusion between revolutions and mass protests, coups, civil wars, riots and rebellions. All of the previous can effectively occur (and often do occur) without the existence of a revolution. They do often accompany revolutions, yet they are not revolutions in and of themselves.

For a minimum outline, a set of at least five questions about revolution needs to be answered:

– Who will make it? The people, the class, the revolutionary party, the vanguard?

– What for? For power, to enact a regime change, to change the political system, to change the economic system?

– How will they make it? By accumulating more political strength than the system, through violence, through speed and surprise?

– What will it be like? Will they take over the state, create a new state, create a new organisational structure for society?

– What will the result be? Will it create a new space of sovereignty, a new nation, expel colonisers, distribute power, change the social order?

All of these need to be answered in the development of a revolutionary theory.

I will cut short the debate around political revolution and social revolution. In our context of climate crisis, a political revolution is unequivocally insufficient for the major shifts required, and as such I will use revolution as a synonym of social and political revolution combined.

Broad schematics

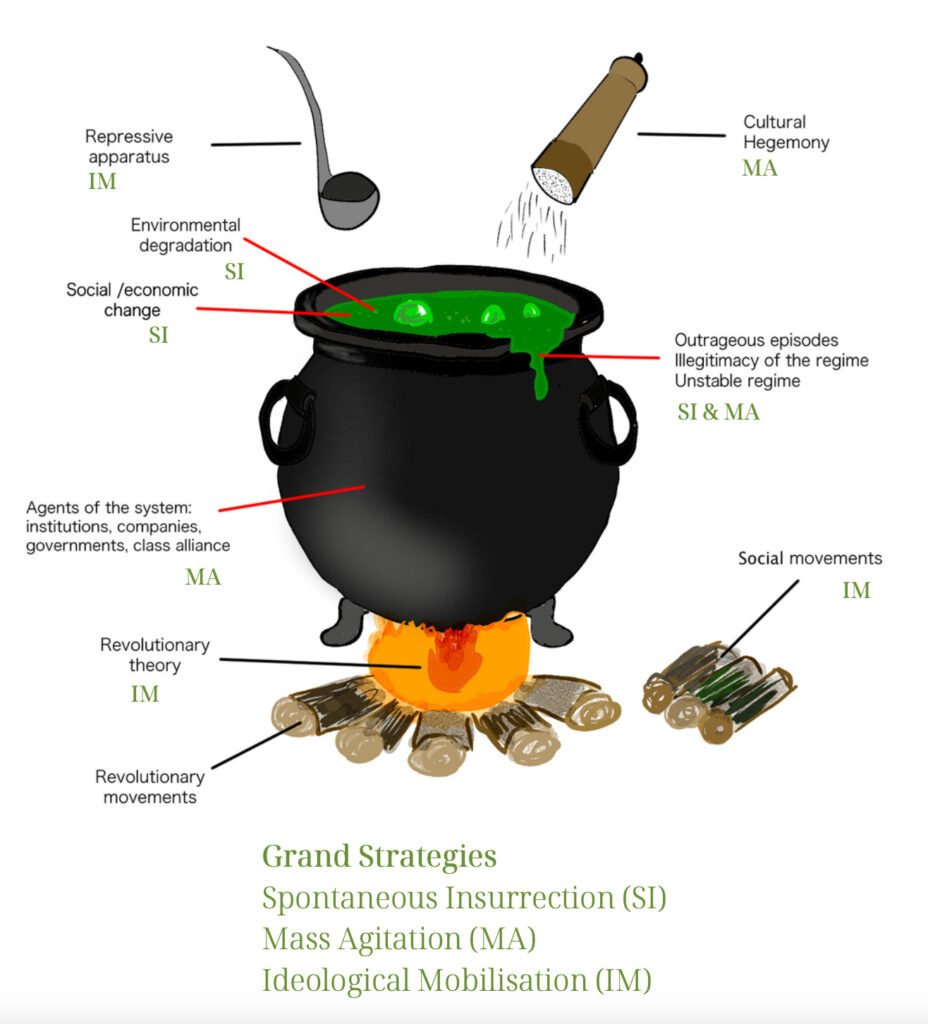

Looking into the multiple factors that perpetuate the capitalist system and the social and political forces that hold or make it unstable, we can project a cauldron of revolution, allowing us a clearer if not perfect view on how to strategically think about system change and revolution.

There’s a traditional Marxist division of objective and subjective conditions for revolutions, where the working class is the revolutionary agent:

– Productive forces must reach a certain level of development to permit socialism to replace capitalism (objective);

– The social position of the working class in the economy must allow it to launch a revolutionary process (objective);

– The working class must be prepared to carry out the revolution (subjective).

Retrospectively, this theory has been tried and failed, or is at least very incomplete. Many times objective conditions were and are still met, and often the subjective conditions were met, and there hasn’t been an global workers’ revolution. Often, these objective and subjective conditions led other classes to quash revolutions; workers have more than once turned to reactionary politics and revolutionary situations have come and gone without revolutionary action. Instead, revolutionary situations, linked to the frequent crises in capitalism, have actually been taken up by other entities and classes, blocking the perspectives of a progressive world revolution to abolish the exploitation of labor. When the expected revolutionary subject wasn’t ready or willing, others have always taken over the opportunities.

The “objective” and “subjective” conditions also account very little for the system’s ability to receive, adapt and co-opt shocks and menaces. I propose a broader set of conditions, increasing their scope.

The Cauldron of Revolution

Today, the stability of the system is based on cultural hegemony, institutional power and the repressive apparatus of the state and capital. All of these are strictly intertwined and are themselves an equilibrium of forces between local, national and multinational capital, institutions and repressive forces. Simplifying, they are the structure of the system, the base of the cauldron.

The ebullition of revolution has always had a base in the imbalances between this equilibrium. They can derive from:

– social and economic shifts (migrations, industrialisation, unemployment, poverty, austerity, war);

– environmental degradation (natural disasters, great destructions, famines);

– political shifts (perception of illegitimacy of the political actors, of the elites, of the institutions, outrageous episodes both within and internationally)

All of these, inside the cauldron of revolution, evolve over time, interacting and reacting among themselves. The system looks for ways to accommodate the contradictions with minor or major adjustments to reestablish a capitalist equilibrium.

Outrageous episodes in society, in politics and in institutions weaken the system. They create the conditions for an illegitimacy of the political regime (yet much less frequently of the economic system). The persistence of the episodes weakens the leadership of the regime, making it unstable and ripe for substitution. Yet, the cultural hegemonic apparatus serves as a permanent cushion, an inhibitor of a certain type of reactions against the status quo, and promoter of others. When there is a shift in the cultural hegemonic apparatus, the capability of containing instability is very low. It is in between these imbalances that social movements and revolutionary movements operate, increasing the temperature and promoting more interaction between the imbalances.

Social movements and revolutionary movements

Historically, the plans and actions of social movements to increase their power can be grouped into three major grand strategies (you can look up the Strategy Stuff videos for more detailed descriptions):

– Spontaneous uprisings;

– Mass agitation;

– Ideological mobilisation.

The main idea is to either have more participants or increase the capacity of action of the current participants, reinforcing the organisation and its cadres. For this purpose, there is a choice made by movement, either conscious or unconsciously, between organisation or themes.

Spontaneous uprisings: Here, the grand strategy focuses on themes, when movements choose to take position on a theme so strong that the population rises in an explosion of support. Yet, the movement has little control on how the participants act or what they will do afterwards. These are the famous “jumps” that also accelerate the responses from the system. The storming of the Bastille is a clear example.

Ideological mobilisation: The grand strategy focuses on organisation and the movement doesn’t expect the population to act spontaneously. People are recruited by the movement, and the recruitment is followed by an extensive ideological training on the themes. The movement generates actions against institutional power in a regular and permanent way, as well as when there are opportunities. The Chinese Revolution and the Irish Republican Army are examples of this.

Mass agitation: A combination of focus on organisation and themes. When there is a general discontentment but no organisation or possibility for an explosion of support for the movement, it creates a vanguard that radicalises using a strategy of themes, while organising effective actions. These vanguards provide examples of what the actions are, influencing masses to align with the movement. The Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 is probably the most successful episode of mass agitation.

These are obvious simplifications of what social and revolutionary movements do, as they often shift tactics, strategies and grand strategies. An excessive focus on any of them will lead to negative outcomes for success as all movements suffer the consequences of their purposeful or unintentional choice:

– A great focus on spontaneous uprisings can lead to explosions without consequence, to social and political decompression and to cynicism and hypocrisy in society.

– A great focus on mass agitation can lead to vanguardism and substitucionism (the idea that a small group can substitute the people in program and action).

– A great focus on ideological mobilisation can lead to isolation, self-sufficiency, alienation and sectarianism.

Social movements are the sectors of society which are already mobilised and in a “stable” society they are very close to the dominant cultural hegemony. They include movements, unions, parties and NGOs, and generally have strong and divergent cultures and practices among themselves.

Nowadays, social movements are not all revolutionary movements, although historically they are one of the main sources of revolutionary leaderships. As such, the grand strategies can and are mostly applied for non-revolutionary purposes, such as promoting the change of a policy, the end of a repression or the removal of a government considered to be illegitimate.

For social movements to turn into revolutionary movements, there needs to be a radicalisation that is often accompanied by a revolutionary program. People argue through a revolutionary theory which tells the movement how to do the revolution itself and what should happen after the revolution. This theory tries to predict the equilibriums and imbalances within societies, the alliances, actions, mobilisations and reactions from power, creating different scenarios. People think about the stages of action (national, regional, global) and possible sequences of events to reach the outcome of a victorious revolution. To achieve the transformation of social movements into revolutionary movements, the grand strategies of mass agitation, but particularly ideological mobilisation must be taken.

Grand Strategies and the Cauldron of Revolution

The imbalances within the system need to be acted upon, and not all grand strategies apply to all moments.

Outrageous episodes present short windows of opportunity, trigger events that facilitate spontaneous uprisings, increasing the instability of the regime, creating cultural impacts that shake the hegemony and radicalize the people or the class. Political shifts usually lead to outrageous episodes such as the attempt to steal the cannons from the Champ de Mars before the Paris Commune, or when new taxes were imposed on the American colonies after the war, or when the rise in the price of gas in France led to the Gilets Jaunes. Many outrageous episodes are fabricated and they are not a sufficient condition for a revolution.

The illegitimacy of the regime is often created by a succession of outrageous episodes or reiterated practices that destroy the social mandate of the elites – including violence and repression. As examples, we can look at most of the monarchies that were overthrown in Europe, Argentina’s expulsion of the president Fernando de la Rua or the protests against Aleksandr Lukashenko in Belarus. The illegitimacy of the regime is reinforced by grand strategies of mass agitation and spontaneous uprisings and is constantly being created by all of those against the present equilibrium. It can break the cultural hegemony and it has cultural impact. It is not a sufficient but it is a necessary condition for a revolution.

A frail or unstable regime can be provoked by internal pressures (social, economic, political conflicts) or external pressures (wars, invasions). This is the case in which there is already illegitimacy of the regime, as the cultural hegemony is not overwhelming enough, so the imbalances are much more difficultly opposed. As examples, we can look at the case of Kerensky’s Provisional Government in Russia in 1917, the social revolution in Spain against the elected government in 1936 or the Turkish revolution after the English troops entered Constantinople. Mass agitation is the key grand strategy in such a situation to advance towards a revolution.

Cultural hegemony is currently the biggest anchor of the capitalist system and its regimes. It provides a combination of alienation and conformity. It is exercised by the intellectual elites, that repeatedly show the dominant vision of the world, excluding alternative visions (by culture and repression). Cultural hegemony determines what is and is not acceptable for most people, being guaranteed by institutions with many faces and agents: the press, social media, schools and the justice system. They have an overwhelming capacity of annulling imbalances and neutralising grand strategies for revolution and even for smaller changes. Mass agitation is the most effective way to counterbalance the cultural hegemony.

The system strikes back

The first thing and the main way the system fights back always begins with the attempt of co-option of any social movement that displays capacity for power, no matter the grand strategy that it adopts or its final objective.

The movement coerces power by interrupting normality, and forces the system to act in order to reinstitute the equilibrium order. This interruption can be physical, political or cultural (or all combined). Many social movements try not only to measure up to institutional power, but also to reach to the whole of society.

The clashes with system power proceed, usually in the following sequence:

Cultural clash: in the media, social networks and cultural spaces, the system attacks the movement to reaffirm the hegemony;

Political clash: the government, the political forces of the regime, counter-revolutionary forces engage the movement, if the movement holds out against the cultural clash;

Organizational clash: the police, armed forces, the justice system try to achieve the annulment of the movement.

The repressive apparatus is usually the last resort, the ladle in the cauldron used to try and dissipate the contradictions by force (it also increases instability).

The system tries to block the action of the movement when it understands that the cost of suppressing it is smaller than the cost of conceding to demands. In the case of revolutionary movements, violent suppression is always the choice, leading to a necessary shift in the movement’s strategies, towards ideological mobilisation and radicalisation.

A clearer view

Understanding a broad schematic of revolution, the main grand strategies of social movements and how the system reacts is essential for us. The cauldron can help provide a clearer view of what we are up against, what strategies we use to organise and what we and others need to do next – that will be the topic of an article in the next issue.