New IPCC Report and Adaptation: from systems transition to transformative worldmaking

BY OSCAR MOONEY

“We cannot adapt to starvation. We cannot adapt to extinction. We cannot eat coal. We cannot drink oil. We will not give up”- Vanessa Nakate

Nakate describes the divergence between the reality of climate change and what is currently occurring under climate policy around the world. Adaptation was the central theme of the recent AR6 WGII report. Words prescribed onto page detail an ever dying planet, its invaluable ecosystems, the people interdependent on them. Having been adopted by climate and ecological researchers for decades, this report brings systems theory to the fore of climate discussion. Just as systems theory has been used to bridge existing disciplines and understandings of the world, this report must be recognised as a bridge between the data-drive world of information to a world of sense-making that can be described only through experiential knowledge and wisdom.

A dire injustice of climate change is that those closest to, dependent on, and defending nature are also experiencing the most adverse impacts of the climate crisis. These are the Indigenous Peoples and labourers across the world, the people of small-island states, and the “Global South”. This IPCC report attempts to describe their world and their knowledge while highlighting the failure of institutions, governance, and finance of rich countries orchestrated by the capitalist and colonial beneficiary’s often living, and originally from, the “Global North”. Within this given systems theory framework we must understand what a systems transition truly means if we are going to transform our world systems from being hellbent for planetary destruction or to re-embed and connect with the knowledge systems of those often forgotten and being left behind.

Starvation and extinction of people, cultures, communities and ecosystems is occurring now at an ever-increasing rate, and when we consider that the practices and technologies to decarbonise have long existed, what exactly is it that this report asks us to adapt?

On Data and Models:

“All models are wrong, but some models are useful”

Climate change has been known to be occurring since the 1970s, yet for many people without an ecological sensibility, the impacts of climate change have been hard to predict. A warming planet, melting glaciers, and rising sea levels are the more classical understandings of what will occur due to climate change. However, the popular recognition of these salient effects of climate change also stems from the western-centric imagination. These classical interpretations of the risks of climate change are cautionary and while true, descriptive of a slow-onset and detached process that does not interrupt peoples everyday lives. These visual descriptions are truly different from how climate change was occurring in more vulnerable countries, the “Global South”. In western liberal-modernist societies primarily concerned with individualism and availability, how did the hierarchies within these capitalist societies react to these early warnings?

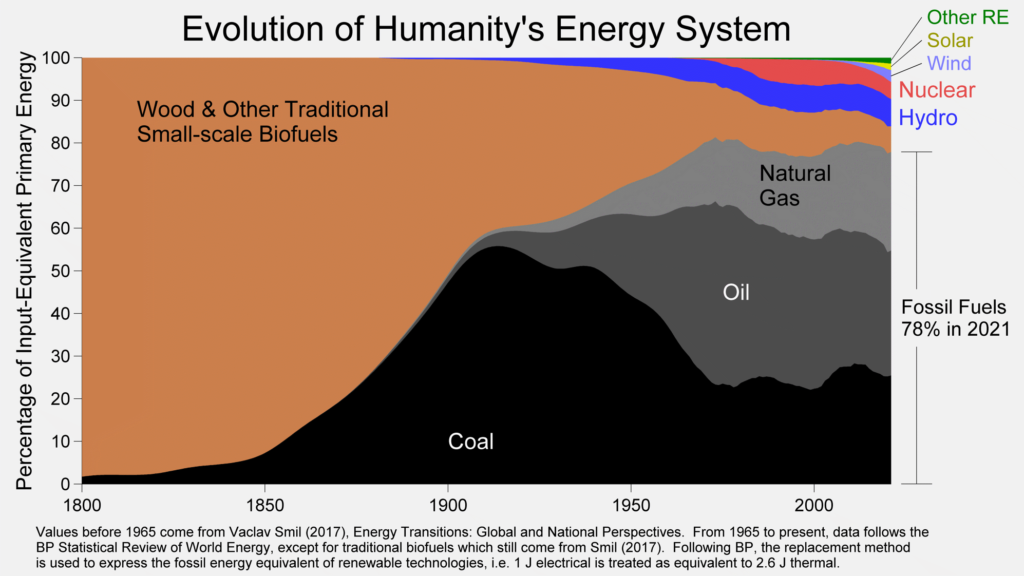

Well, to ensure the maintenance of their capital flows they set to work on financing climate-doubt and the creation of lobby groups, but also through the corruption of rationalisation. In truly apathetic rationality, if climate change could not be proved then it was not happening – especially since dealing with climate change would be bad for business. In the western world, an epistemic battlefield between climate scientists and the “rational agents” of growth-based economies assumed ensued. These debates were held in the media, in educational institutions, and in international conferences concentrating on the science while the latter group continued to ignore the deterioration of ecosystems and suffering of people due to climate change. The indifference towards people and the natural world, while doubt-led distractions occurred across economics, climatology, ecology, and political science, meant that the climate crisis as it has come to be understood had its epistemological genesis in the neoliberal mandate for the 21st century.

Consequently, collated information from the world’s top climate scientists has been aggregated into the IPCC reports. Within these reports, climate and ecological models have widely been employed. These models utilise the mathematics understood of climate and ecological science to predict the affects that climate change will have. These have been used alongside measurements of sea and air temperature increases, coincided with increases in carbon dioxide levels, to prove that climate change was occurring. These models, scientific findings, and various efforts to communicate through media have now broken through the fog of doubt created by fossil fuel capitalists, but this was not done by climate scientists alone. For many people, these reports have described a world already known and or experienced by them. The centering of scientific doubt in climate debate removed, and relied upon the continuos dehumanisation of, people who colonialism and capitalism have historically oppressed.

Effects from the report:

An increase of two degrees Celsius will see almost one fifth of terrestrial species assessed in the IPCC report face extinction. Biodiversity is most vulnerable to increasing temperatures in ocean and coastal ecosystems. Consequently, the rate of extinction is increasing exponentially, and will continue to, depending on what temperature increase our planet sees. Above and below ground, terrestrial and aquatic, all our ecosystems are threatened by climate change. Unique and threatened systems include natural systems and the people who rely on them, such as the Arctic and its Indigenous People.

Sea-level is exposing more and more people to risk of coastal flooding, while being an existential threat for small-Islands states and low-lying coasts. Furthermore, climate change has been increasing food insecurity in these ocean-reliant states as well as areas such as Sub-Saharan Africa and South America. With malnutrition and nutrient deficiencies as the outcome, these mounting diseases should be considered as climate-sensitive. While densely populated areas have been stated to contribute to ecological degradation this does not concern why areas became so densely populated nor the unequal consumption of resources on the planet. Historic process of urbanisation and land-grabbing have contributed to the vulnerability of those forced into urban areas to find work. Continued and current trends of urbanization will continue to cause increased vulnerability. The agency of the people who live as part of these vulnerable ecosystems was also been eroded by colonial-originating hierarchies.

Economic damages from climate change will continue to compound those low-income countries placing them in a continuous uphill battle. The costs of maintenance and reconstruction in urban areas, as well as energy prices, are expected to continue rising. Many low-income countries have found themselves squeezed between climate change and global debt, as the ruthless competitive global economy has failed to provide necessary international mechanisms for debt cut while ignoring calls for a remedial and reparations-orientated Loss and Damage framework. Historical colonialism is mentioned as one of the contributors to vulnerability however does this report mention anything on how to adapt to this? Unfortunately, no. These issues are raised but left unattended, as if they were natural phenomena without delving into details of their exploitative, historical causes.

Information to experience across interrelatedness of systems:

“The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: What good is it?” – Aldo Leopold

The interrelatedness of organism and environment is the basic unit of survival. If one is threatened so is the other. Very high risk is associated with irreversibility and the limitations of adaptation. The report focuses on the critical risks which an ability to respond to must be fostered. It is how vulnerability, hazards, and exposure come together that contribute to the overall risk which then continues to increase as the adaptive capacity of these systems collapses. The “cascading” affect suggests ecological degradation will snowball as habitats, ecosystems, communities, and countries lose their ability to adapt meaning that as these risks become reality, they will become unrelentless and almost impossible to control.

In situations of risk, adrenaline levels surge, heart rates increase, blood pressure rises, rapid breathing, sweating, and changes in metabolic rates occur. This rushed state of existence – immediacy and anxiousness – is something we have all experienced. When it comes to climate and global change, extreme heat and crop failure, as humans face these existential threats, this becomes the effects of climate change. Increasing global temperatures place increased pressure on agricultural workers around the world, many of whom work for long durations with little protection from the sun’s rays. As areas become uninhabitable, climate refugees are being forced to cross both lands and seas only to be rejected at state-surveilled borders. Consequently, the climate and biodiversity crises should be understood as unfolding on the natural world which in turn subjects the most vulnerable to hazardous working conditions, famine, disease, migration, homelessness, and mental illness and anxiety.

Just as the climate crisis demonstrates the interrelatedness between people and planet, it also reveals the interrelatedness between the biosphere and the inability of capitalism to respond in a systematically appropriately manner, while potentially exacerbating these problems further. An example being that just as the commodification of food has already lead to poverty and famine, the climate and ecological crisis will further increase food prices and food insecurity leading to those with low incomes, many of whom are global agricultural workers, suffering the most.

We know that changes and impacts will occur, but it is how we adapt that can change the vulnerability of natural and human systems. Closeness to nature has become a vulnerability, but it is also a practice and way of life through which we can learn to adapt to climate change. This highlights our reliance, dependence, and relationship on our surrounding environment. The dominance of science as the communication medium for climate change does not mean that more experiential understandings of climate change are not valid. In fact, that is exactly what this report calls for – that a greater centering of these voices and knowledge systems is required for true adaptation.

The Information to Knowledge and Wisdom Shift:

Resilient power systems and energy reliability, along with Terrestrial and ocean ecosystem adaptation, such as forest-based adaptation, agro-forestry, and biodiversity management, are all regarded as feasible and synergistic with mitigation efforts – this can be considered a win-win in climate action. However, when we look at the other challenges and their feasibility, human migration is regarded as having a medium synergy with mitigation, and planned relocation and resettlement has the lowest overall feasibility with mitigation efforts. Institutional feasibility across

all areas of the required adaptation measures is medium to low. Incremental, sector-specific, adaptation cannot respond to the scale of the multi-dimensional crisis we are facing.

Low-to-no adaptation includes fragmented, localised, and incremental adjustments to existing practices. The report says that “larger adaptation gaps exist among lower income population groups”. This stresses how communities, regions, and whole regions that were economically disadvantaged from periods of industrialisation and colonialization are now most at risk. These processes resulted in the financial constraints that prevented improvements in societal and social structure, while many were further compounded by their climate-vulnerable geographical locations. This adaptation gap will continue to grow as adaptation requires time, long-term planning, and finance. The issue of feasibility is that most of these measures will not be profitable, their value is adaptation itself, which is contradictory with the global capitalist economy.

The IPCC report authors explicitly express the shift from information on predictions and projections of climate change to a knowledge-based approach required for the integration between climate, ecosystems, and biodiversity and the various spheres of human societies. This requires a shift in governance, finance, technologies, knowledge, and capacities. At the heart of this transition process for both planet and people the authors suggest “climate resilient development”, with health, well-being, justice, and equity at its centre. This requires that these values be extend to both people and planet as they are the material conditions that have been left out of considerations in order to achieve ever increasing profits and economic growth.

Many adaptation measures only alleviate near-term climate risk reduction. These in turn can decrease the opportunity for transformational adaptation. Therefore, these measures do not target the heart of these matters. As they do not target capitalism, financial availability becomes a prime factor in an adaptation measures feasibility. This becomes increasingly more unsettling given that it was through financialization, commodification, and dehumanisation that the climate crisis unfolded. Limiting adaptation measures by the same economic system that proliferated the climate crisis is itself an act of maladaptation.

Conclusion:

Behind the technical systems language of the paper, political language that has long been suppressed by techno-optimism seeps through. Following this digression, the critical interrogation required to undo these past and current malignancies demands to rise to the surface. Colonialism, Loss and Damage, and human and natural well-being describe the processes and events that construct the climate crisis as well as what is required to confront it. The values required to solve the climate crisis cannot be those which caused it. Racism, capitalism, and greed are all antithetical to the worldmaking needed.

The colonial world was steeped in the dehumanization and “othering” of Indigenous Peoples in the countries Europeans colonised. As these places were colonised for exploitation, the visioning that nature was something to be exploited translated into oppressive disregard of the Indigenous People in those places too. This hideous misunderstanding created the foundations for forging the international economic relations that still serve the economic accumulation of the wealthy of today’s world. Those hierarchies that formally became institutions, governments, and financial rules were founded on social constructs for maintaining these oppressive colonial relations which have now led us to the precipice of planetary collapse.

But just as each cog turned in history has shifted us towards the present, we must re-imagine, re-learn, and abandon those malignant processes that will only further destroy our shared future. Adaptation of human and natural systems needs to shed its technical blockades. The western-centred ideologies that have brought us to this crisis are what need to be changed. Critiques fostered through ethnic, race, gender theory, and socialist thought have identified the transformation that is needed while Indigenous wisdom provides the knowledge to heal the Earth.

To adapt a world currently being destroyed by greed, colonialism, and dehumanisation to one of equity, well-being, and justice, it is important to consider what exactly it is we need to adapt. Climate change is the material outcome of epistemic violence, just as global capitalism emerged as the economic system from colonialism.

Adaptation suggests a modifying of a system, but here the authors explicitly mention a systems transition. This means getting rid of the previous systems and moving towards a new one. With the foundations, values, and outcomes of this new system all antithetical to the capitalist system of colonialism, this report tells us that systems change is not just warranted but needed now.

Oscar Mooney is an Irish climate activist and ecosocialist involved with non-violent direct actions as part of Extinction Rebellion Ireland. Grateful for the writings and actions of revolutionary thinkers and activists while frustrated with the commodification of social and natural life, he is engaged in movement-building towards a people-led Just Transition with wellbeing, redistribution, and reparations central to a new justice-orientated and solidaric world.